Grove Koger

May 31 is the birthday of French artist Jules Chéret, who was born on this day in 1836 and whom I profiled for the Summer 2015 issue of the late lamented Laguna Beach Art Patron Magazine.

□□□

There may be any number of avenues to fame and fortune, but being in the right place at the right time is hard to beat. As it turned out, being in Paris in 1866 turned out to be the right combination for Jules Chéret, who set up his lithographic printing business in the French capital that year.

Chéret had been born there thirty years before. Apprenticed to a lithographer when he was thirteen, he also took a course in drawing at the École Nationale de Dessin in Paris, and spent his spare time in the city’s art museums, learning what he could from the masters.

Dissatisfied with selling sketches to music publishers, Chèret moved to London, where he found making drawings for a furniture company equally unfulfilling. Back in Paris, he secured a commission to design posters for Jacques Offenbach’s 1858 operetta Orpheus in the Underworld. Chéret’s artistic vision was a match for Offenbach’s frothy musical one, but the venture came to nothing, and in 1859 he returned to London, studying English color lithography techniques and supporting himself by designing book jackets and music hall posters.

It was in London that a mutual friend introduced him to Eugene Rimmel, a perfumer who hired Chéret to design labels and scented Valentine cards. Impressed by the artist’s talent, Rimmel helped him set up business in Paris (this was in 1866, remember), and even arranged the shipment of color lithographic presses, which were then unknown in France.

We’re used to thinking of Paris as the “City of Light” without wondering what the words might actually signify. But it really did earn the title in the 1860s, for it was during that decade that the French capital became one of the first cities in Europe to install gas street lights—some 56,000 elegant wrought iron affairs that illuminated its streets and boulevards. The Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 proved a humiliating disaster for France as a whole and Paris in particular, but the subsequent peace brought stability and prosperity. It was the beginning of what would be remembered later as the Belle Époque, a decades-long era of optimism and vital artistic expression—and pleasure.

Parisians who could afford to do so—and there seemed to be more and more of them—patronized cabarets such as the Moulin Rouge and the Folies Bergère. Those with pretensions to higher culture enjoyed operettas and operas. There were casinos where they might gamble away their money in style and restaurants such as the Ritz where they could consume the very best haute cuisine. What’s more, women of the Belle Époque could study in universities, dress more provocatively, even smoke.

And in the middle of this hedonistic tumult was Jules Chéret, who was positioned to become one of the age’s best chroniclers. His chosen medium, lithography, involves using grease pencils and crayons to create a water-repelling image on a slab of porous stone. Gum Arabic and a weak solution of acid are then applied to the stone, fixing the image while rendering the areas outside the image water-retaining but ink-repelling. Next, the stone is wetted and inked, and finally the image is transferred to a sheet of paper pressed firmly onto the stone.

Unlike other artists, who turned over their work to a lithographer to complete, Chéret drew his designs directly on the stone himself. The resulting spontaneity is obvious in his posters, which are the artistic equivalent of Champagne. Chéret had studied Victorian graphic design during his years in England, but he rejected its fussiness in favor of a broader and freer approach, utilizing two and then three stones for a maximum range of colors and textures.

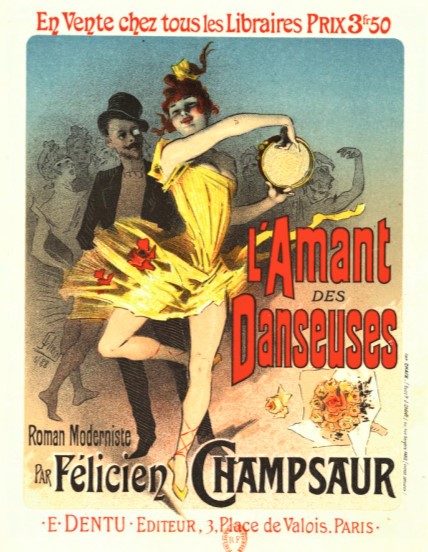

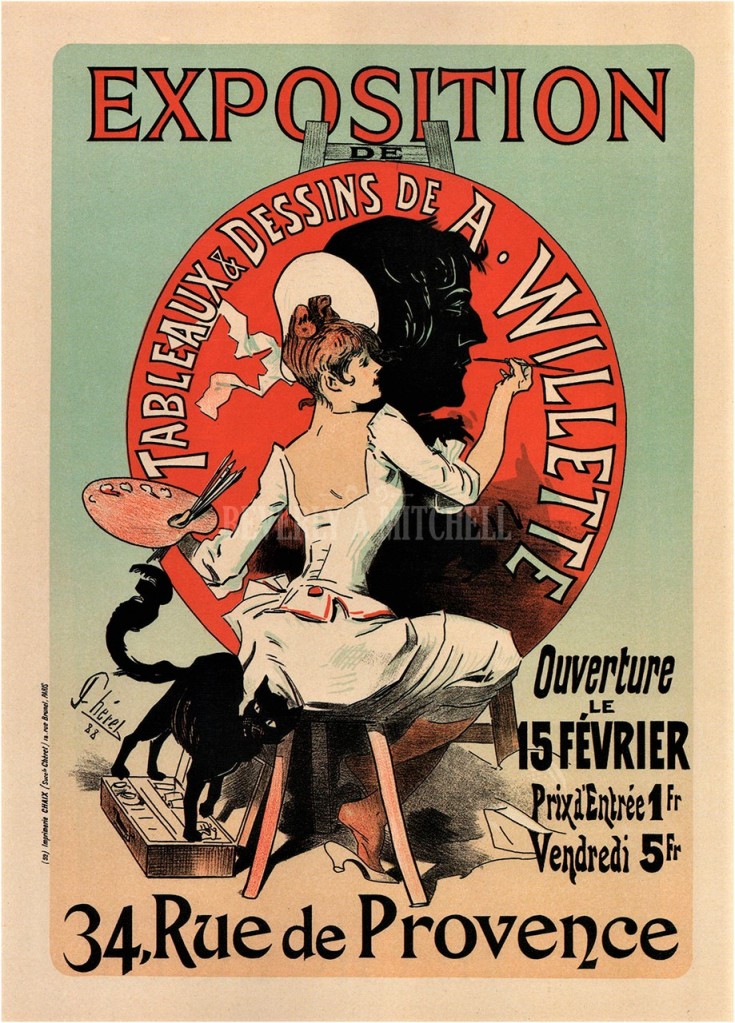

As an artist, Chéret combined the grace and exuberance of eighteenth-century Rococo with the freedom and spontaneity of his own century’s Impressionism. His subjects ranged from music halls to novels and magazines, from liqueurs to cigarette papers (particularly the Job brand) to lamp oil. His designs were bold and colorful, and almost always featured one of the elegant, fun-loving damsels who inevitably became known as “Cherettes.” Whatever the subject or the design, pleasure was the message, and it was a message eagerly endorsed by the French public.

During his lifetime, Chéret created more than one thousand vivid posters, and was rewarded with membership in the prestigious Légion d’Honneur in 1890. He eventually retired to the Mediterranean port of Nice and died at the ripe old age of 96, having lived a life full to the brim.

If you’d like to subscribe to World Enough, enter your email address below:

And if you’ve enjoyed today’s post, please share!