Grove Koger

What’s the best adventure novel ever written? Answers might include Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island (1883), H. Rider Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines (1885) or She (1887), Anthony Hope’s Prisoner of Zenda (1894), Baroness Emma Orczy’s Scarlet Pimpernel (1905), John Buchan’s Greenmantle (1916), James Hilton’s Lost Horizon (1933), and C.S. Forester’s African Queen (1935). Among authors with greater critical standing, we could include Charles Dickens for A Tale of Two Cities (1859), as well as André Malraux for The Royal Way (1930). Among writers closer to our own time, Lionel Davidson’s underappreciated Rose of Tibet (1962) deserves to be in the running.

But the very best? I’d nominate Percival Christopher Wren’s novel Beau Geste, which was published by John Murray in 1924, almost exactly between the dates that Treasure Island and The Rose of Tibet appeared.

Wren’s novel opens with a mystery. Major Henri de Beaujolais of the Spahis (French light cavalry regiments) has come upon a fort—Zinderneuf— deep in the Territoire Militaire of the Sahara Desert manned by dead soldiers of the Foreign Legion. Their bodies have been arranged on the fort’s ramparts, as if they were still defending it from attack. The major also finds the fort’s dead commander, a bayonet in his heart and a letter in his hand. It’s a mystery indeed!

The scene then shifts to the English country house of Brandon Abbas, where the three Geste brothers—Michael (known as “Beau”), John, and Digby—live with their aunt, Lady Patricia, along with two young women, Isobel and Claudia. One evening, Lady Patricia is persuaded to bring a beautiful jewel, a sapphire known as the “Blue Water,” out of hiding for all to admire. But then the lights suddenly fail and the group are plunged into darkness. When the lights come back on, the jewel has vanished!

Now that Wren has set up a second mystery, the Geste brothers vanish, one by one. Could anything be more suspicious? We follow the three as they join the French Foreign—apparently the obvious choice in those days for red-blooded young men in desperate straits—and serve beside each other in North Africa helping fight France’s colonial wars. Eventually they’re posted to Fort Zinderneuf, where some of the book’s mysteries are solved.

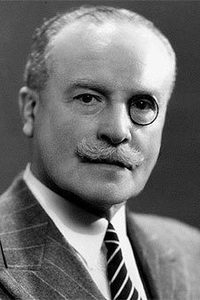

We know a few facts about Wren’s life, but there are tantalizing lacunae that will probably never be filled. Wren himself supplied some details, and his publishers supplied more, but some are too good to be true.

Wren was born in London on November 1, 1875, and died on November 22, 1941. He attended what’s now known as St Catherine’s College, Oxford, a fact that sounds a bit posher than it really was, as the school had been established in 1868 for those who couldn’t otherwise afford the university. According to his comments in his entry in the 1942 edition of Twentieth Century Authors (Wilson), he subsequently spent five years travelling and working as a “’sailor, navvy, tramp, schoolmaster, journalist, farm laborer, explorer, hunter, and costermonger in the slums.’” Exactly what his accomplishments as an explorer might have involved he left unexplained.

Wren married Alice Shovelier in 1899, and she gave birth to a daughter, Estelle Loren, in 1901 and a son, Percival Rupert Christoher Wren, in 1904. Wren himself joined the Indian Educational Service (IES) and in 1904 was appointed headmaster of the Narayan Jagannath Vaidya Government Higher Secondary School in Karachi, a city then in India and now in Pakistan. It was a position he held until 1906. During this same time, he also served with the Educational Inspectorate for Sindh, the province that includes Karachi.

Like many children of English couples living in India at that time, Estelle was sent “home” to England at some point, and she died there in 1910. Alice Wren herself died four years later. Wren resigned from the IES in 1917 and sometime afterward, as he would claim for the rest of his life, he joined the French Foreign Legion. And it’s precisely here that serious doubts arise, as no one, including Wren himself, has ever provided a shred of evidence for his service in the Legion. His name never appeared on its rolls (although, admittedly, he claimed to have enlisted under a false name), no fellow legionnaire ever referred to him, and no photographic evidence has ever been produced.

As Jean-Vincent Blanchard concludes in At the Edge of the World: The Heroic Century of the French Foreign Legion (Bloomsbury, 2017), “In all likelihood, Wren never joined the Legion, and he drew on the memoirs of George Mannington and Frederic Martyn.” Mannington’s book A Soldier of the Legion: An Englishman’s Adventures under the French Flag in Algeria and Tonquin was published in London by John Murray in 1907, and Martyn’s memoir Life in the Legion, from a Soldier’s Point of View was published in London by G. Bell four years later. Although I haven’t read it, the latter account apparently describes an incident that could easily have inspired Wren’s account of the perplexing situation at Fort Zinderneuf. In any case, as Wren published his novel in 1924, he would have had ample time to obtain and read the two books.

Where might we have found the fort? The question is a bit more complicated than you might think. In the novel’s first chapter, a character refers to the “little post of Zinderneuf” as lying “far, far north of Zinder.” And in the second chapter, another character remarks that the fort itself is in French Soudan. Well, the city of Zinder actually exists, and during the period in which the novel is apparently set, it lay in the eastern area of what was indeed the colony of French Soudan. Around the turn of the twentieth century, the French reorganized the area as the separate colony of Niger, and in 1960 it became an independent nation. So … my guess is that Fort Zinderneuf lay near the northern border of what’s now Niger. (You can see Niger and Zinder near the eastern edge of the map of the federation of French West Africa, above.)

In Visions of Yesterday (Routledge & K. Paul), which discusses the first three motion picture versions of the novel, Jeffrey Richards writes that Beau Geste “dramatizes those attributes of a good public schoolboy—loyalty, comradeship, self-sacrifice, duty and honor.” Wren would undoubtedly have agreed, but we should remember that in England, a “public school” is actually a costly private one—the kind that Wren was able to attend only under special circumstances. Would his memories of his social and economic situation at St Catherine’s have rankled?

The Geste brothers’ heroic self-sacrifices may strike more sober-minded readers as being out of proportion. Yet somehow they add to the book’s appeal, although they probably resonate most strongly with adolescent readers—and with the adolescents still lurking in the hearts of many of us. Which leads us to another question: Did an adolescent lurk in Wren’s heart as well?

The image at the top of today’s post is the cover of my 1960 Permabook copy of Beau Geste. The cover of the 1994 Wordsworth Classic edition showing the Legion in action in Algeria is reproduced from the Sunday supplement to the June 14, 1903, issue of Le Petit Journal. The map of French West Africa is reproduced from the February 29, 1936, issue of L’Illustration, and the French West Africa stamp showing a landscape in Niger dates from 1947.

□□□

If you’d like to subscribe to World Enough, enter your email address below:

And if you’ve enjoyed today’s post, please share!