Grove Koger

In this post I’m concluding my 2014 review “A Favorite of the Gods” from the now-defunct Philadelphia Review of Books. A week ago I discussed Artemis Cooper’s biography Patrick Leigh Fermor: An Adventure. Here I review the final volume of Fermor’s famous trilogy describing his walk across Europe in the early 1930s.

□□□

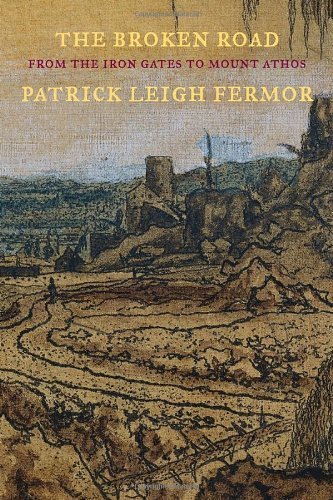

The Broken Road: From the Iron Gates to Mount Athos, by Patrick Leigh Fermor. John Murray; New York Review Books

There’s magic in Cooper’s biography—the magic of a life lived headlong and without overly much regard to consequences—but not in her words. It’s a biographer’s job to be clear-eyed and cool-headed, so for word-magic we must turn to Fermor’s own books, and it’s a pleasure to report that Cooper and travel writer Colin Thubron have been able to assemble the concluding account of Fermor’s walk.

The Broken Road takes its author through the mountains and across the plains of Bulgaria and Romania, then little-known realms of lost tribes, obscure sects, and dying languages. (Surprisingly enough, the former country would also turn out to be “one of the richest natural hashish gardens in the world.”) The book draws in part from a lengthy fragment—informally titled “A Youthful Journey”— that Fermor wrote in the mid-1960s and put aside. The rest comes from a 1935 journal, his so-called Green Notebook, in which he recorded the last leg of his walk and its immediate sequel. He had believed that this journal was irretrievably lost, but it was returned to him one bittersweet night in 1965 by a lover he had been forced to leave behind in Romania at the outbreak of World War II. Fermor reworked passages from both “Journey” and the notebook, but was dissatisfied with the results.

Although disjointed at times, The Broken Road is in many ways a match for its predecessors, and shares much of their joie de vivre. Fermor excels at folding history into landscape, and delights in catalogs of exotic place names and of foodstuffs on tantalizing display in markets. There are bravura celebrations of the natural world, of which the most outstanding example may be his description of an enormous flight of storks, which begins with his sighting “an indistinct blur” on the skyline and concludes, two and a half pages later, with his watching the “long slow swerve effortlessly navigating the invisible currents of the sky, growing dimmer and dimmer until at last they vanished … leagues away down the Balkan corridor.”

Cooper and Thubron include a few of Fermor’s cursory notes about Constantinople, but the book’s final section is set in Greece, on the slopes of “huge, ghostly white” Mount Athos and among its many Orthodox monasteries. Running to nearly one hundred pages, it records Fermor’s first impressions of the country that was destined to capture his heart. It’s also more polished than some of the other material in The Broken Road—perhaps because, as Cooper and Thubron explain in their introduction, Fermor devoted considerable effort over the years to revising and expanding it. Whatever the young man’s ostensible goal may have been when he set out on that rainy afternoon so many months and miles before, it seems that here, at last, he had reached his real destination.

□□□

The cover of the New York Review Books edition illustrated at the top of the page is taken from Landscape with Fir Tree by Dutch printmaker Hercules Segers, c. 1590–c. 1638.

□□□

If you’ve enjoyed today’s post, please share!