Grove Koger

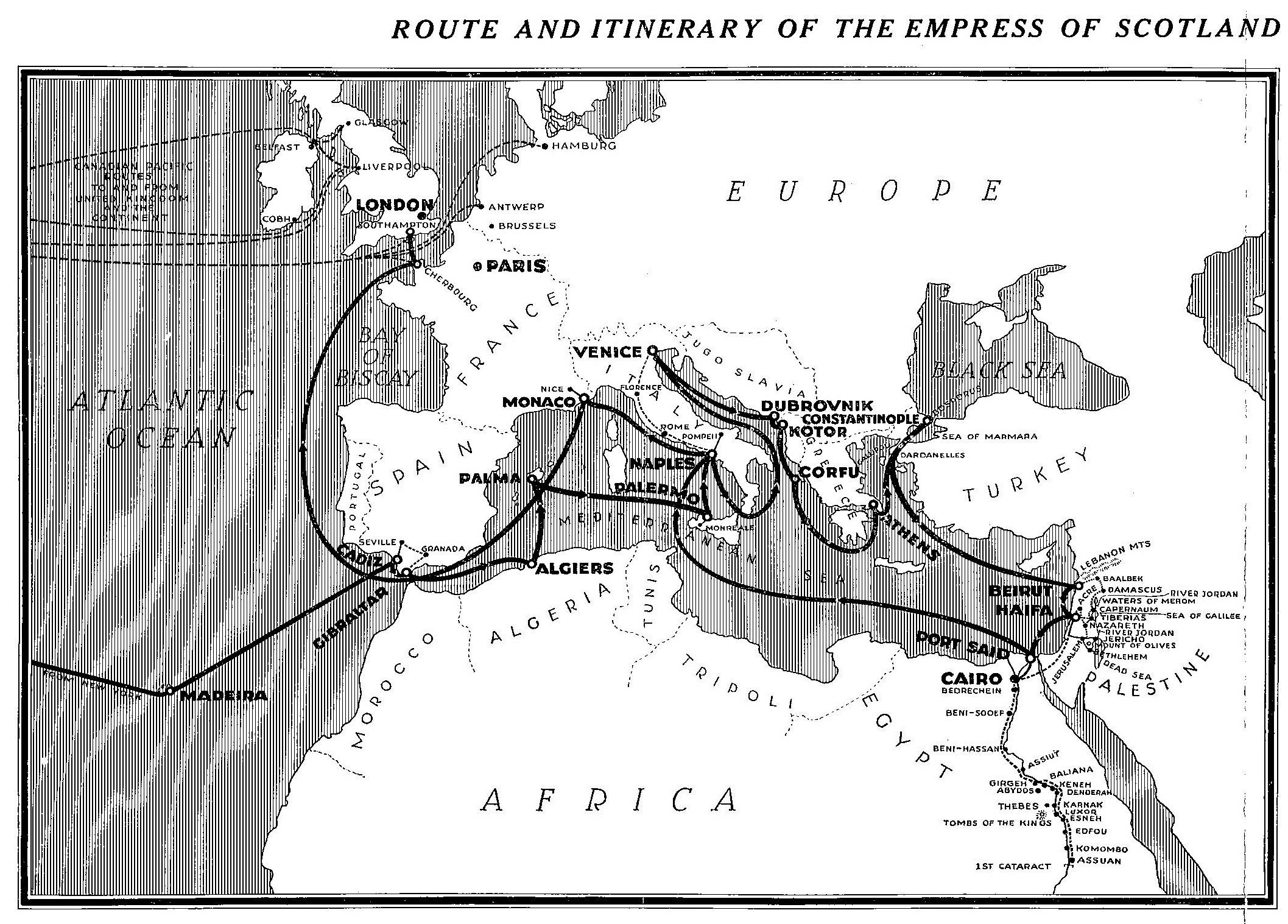

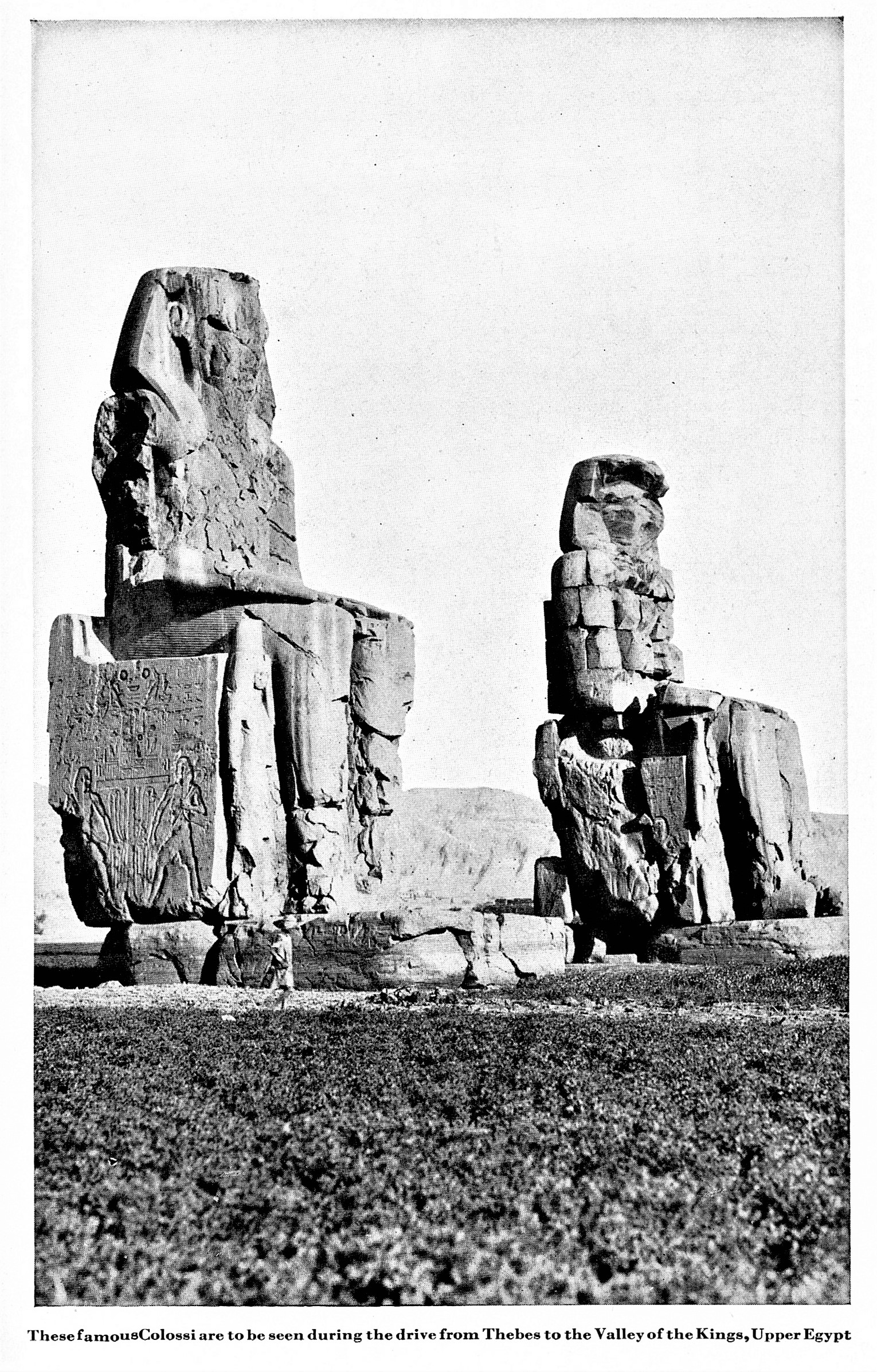

The enormous stone statues known as the Colossi of Memnon lie west of Luxor in Upper (that is, southern) Egypt. Carved from sandstone and erected in 1350 BCE, they face south-southeast, toward the Nile River, and stand, or, rather, sit on pedestals that raise them to a height of nearly 60 feet above the surrounding plain. They were once thought to represent a mythological Greek king known as Memnon, but in fact they depict Pharaoh Amenhotep III.

Both statues have suffered serious damage over time, with the worst resulting from the effects of an earthquake in 27 BCE. It was more than two centuries later, in about 199 CE, that the upper portions of the northern statue were reconstructed with five layers of sandstone by artisans working for Roman emperor Septimius Severus.

If you’re curious, you’ll find more information about the Colossi on the Internet, but my interest is specifically in a curious sound, or “cry,” that the northern statue was occasionally heard to make in the years following the earthquake. The cries generally occurred at sunrise or shortly afterward, with the first recorded instance reported in 20 BCE by Greek geographer Strabo, who described the sound as resembling a slight blow and noted that others had heard it as well.

Subsequent earwitnesses include three Roman figures—general Germanicus in 19 CE, poet Juvenal in 90 CE, and emperor Hadrian (who was accompanied by his wife Sabina and a large retinue)—and a second Greek geographer, Pausanias, who wrote that the sound reminded him of the snapping of a harp-string. The last known occasion in which the mysterious sound was heard was in 196 CE. After the reconstruction of 199, the mysterious cries apparently ceased. Or, as Lord Curzon, former Viceroy of India, put it in his 1923 account Tales of Travel (London: Hodder and Stoughton): “From the beginning of the third century A.D. a cloud of impenetrable darkness settles down upon [the statue’s] fame and fortunes.”

I first read about this curious phenomenon in “The Cry of Memnon,” one of the highlights of Rupert T. Gould’s collection Enigmas, originally published in London by Philip Allanin 1929. After a consideration of all the accounts he could find, Gould concluded that the sounds had their origin in the sun’s “warming the cleft and truncated lower half of the statue; that it was produced by the unequal expansion of the two portions of this fractured monolith—causing them to move, fractionally, one against the other; and that they no longer had free scope for this interplay when they were compelled to support the great weight of the rebuilt upper portion.”

Subtitled Another Book of Unexplained Facts, Gould’s collection follows upon his similar volume Oddities of 1928. Gould (1890-1948) was a recognized authority on marine chronometers, and although I don’t believe he had any interest in the so-called supernatural, he was intrigued by anomalies, including such cryptids as the Loch Ness Monster. He was also an elegant writer, and his works reveal the workings of a sharp and unfettered mind.

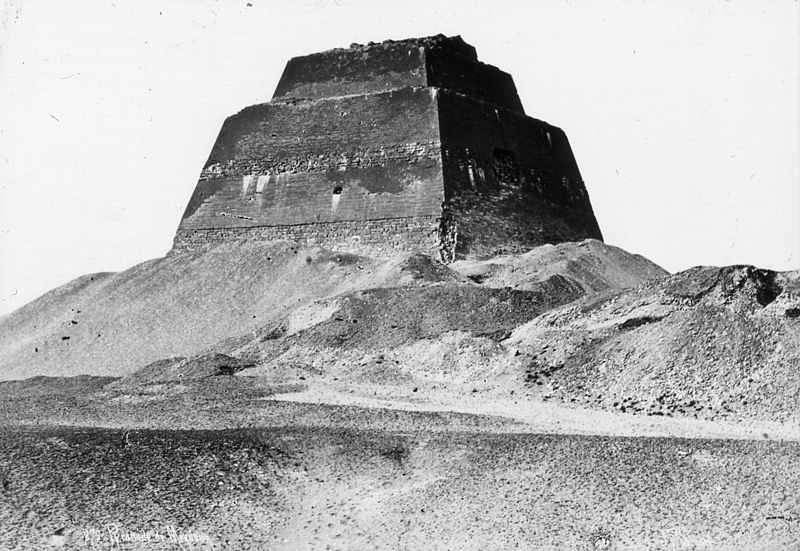

The image you see at the top of today’s post is a nineteenth-century albumen silver photograph taken by Antonio Beato, while the second is an 1846 lithograph by Louis Haghe after a drawing by Scottish artist David Roberts. The third image is my 1969 Paperback Library edition of Enigmas, with a cover by Tom Adams.

□□□

If you’d like to subscribe to World Enough, enter your email address below:

And if you’ve enjoyed today’s post, please share!