Grove Koger

Halloween may be behind us, but as our nights grow longer and darker and colder, I can’t help thinking of the darker strains of folklore and literature.

One of the darkest of these strains involves the Erl King (or Erlking or Erlkönig), a malignant being who steals children. The basis of the story seems to be an old, old Danish ballad known as “Elveskud,” which, in one version or another, involves a man whose encounter with elves ends badly.

Most modern forms of the story derive from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s ballad “Erlkönig,” which the writer originally included in his light 1782 opera Die Fischerin. Here, a father goes out riding one dark night with his young son, only to encounter the Erl King, who steals away the child’s soul, leaving his body lifeless. (The image at the top of today’s post is the fatal ride as imagined in 1911 by Julius von Klever.) The ballad has been set to music numerous times, most famously in an 1815 piece by Franz Schubert. Thanks to YouTube, you can hear a performance (and read an accompanying English translation) with Philippe Sly and Maria Fuller here. Franz Liszt, in turn, arranged Schubert’s piece for piano solo in 1838, which you can hear in a bravura performance by Yuja Wang. (Liszt revised his arrangement in 1876, but I can’t tell you which one the pianist is playing.)

And on and on the settings go, although the horror of Goethe’s dark ballad tends to get lost over time. And it’s that horror that we need to keep in mind, for, during the centuries in which the story arose, most couples were forced to rely on their children to care for them in old age and to carry on their bloodline. The loss of a child was a disaster on many levels.

There are quite a few close approximations of the Erl King story in folklore, and they constitute what we might call the Stolen Child Motif. The most famous of these is probably the story of the Pied Piper of Hamelin, who took his revenge on the townspeople who refused to pay him for luring their rats away by luring their children away instead. (The 1881 interpretation you see above is by James Elder Christie.) Goethe wrote a version, “Der Rattenfänger,” in 1803, as did the Brothers Grimm (Jacob and Wilhelm) in their 1816 collection Deutsche Sagen.

A later version of the motif, dating from 1870, is “The Child That Went with the Fairies” by Irish writer Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu. Here, several children living “eastward of the old city of Limerick” encounter a colorful antique coach drawn by four horses, accompanied by disturbingly “diminutive” attendants, and carrying a beautiful lady and her Black female companion. The story is particularly memorable for a brief passage that absolutely defies reason. I won’t describe it, because it relies for much of its power upon shock, but you’ll find it near the end.

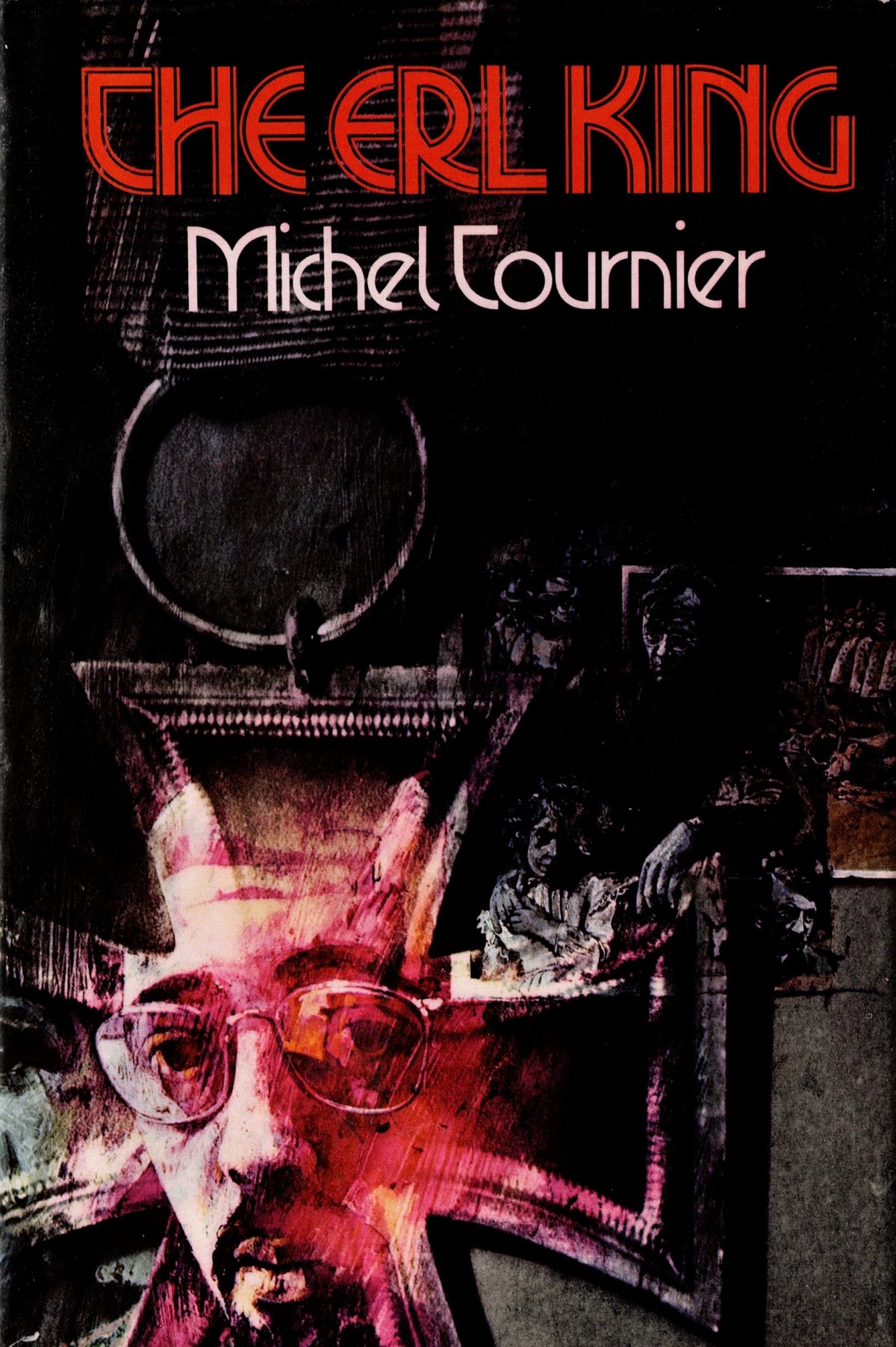

The most recent literary iteration of the story I’m aware of, and by far the most sophisticated, is Michel Tournier’s 1970 novel Le Roi des Aulnes, which was translated by Barbara Bray and published as The Erl King. It was the first novel ever chosen unanimously for the Prix Goncourt, and put its author in contention for the Nobel Prize. In it, a misshapen, simple-minded French mechanic, pigeon-keeper, and apparent pedophile named Abel Tiffauges is taken prisoner by the Nazis during World War II. However, he finds the experience liberating, particularly when he is given the task of recruiting boys to become soldiers—a project in which he believes that he is fulfilling his true destiny. But Russian troops are advancing inexorably from the east and Germany is collapsing …

The Erl-King is a dark and uncomfortable book, and it brings home the horror of the old story like no other version. And that’s the way it should be.

□□□

If you’d like to subscribe to World Enough, enter your email address below:

And if you’ve enjoyed today’s post, please share!