Grove Koger

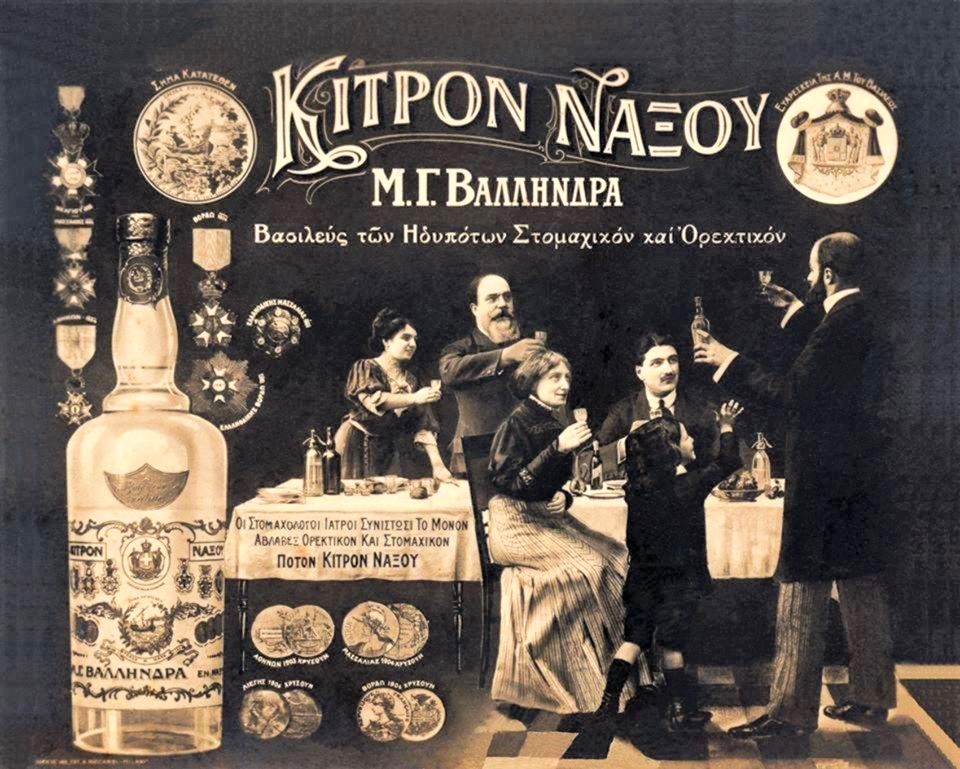

I’ve been fascinated by mastika— or mastiha, as it’s sometimes transliterated into English—ever since my first wife and I visited the little settlement of Ierepetra in southern Crete in the 1970s. A small group of travelers had gathered in our hotel room for a party, and when we ran out of ouzo, I was delegated to buy more. Well, it was late and the light in the little grocery was dim and apparently I was a little dim myself, because when we passed around the new bottle, we had an unpleasant surprise. What we tasted wasn’t the liquoricey ouzo we anticipated but a strange concoction that, on close examination, turned out to be—mastika.

The flavor was so unusual that I became obsessed with it, and over the years I gathered as much information as I could about it and the mastic that gives it its flavor. My essay “The Tears of Chios” is the fruit of that obsession. It appeared originally in Illuminations: An International Magazine of Contemporary Writing for Summer 2013, and was reprinted online by The Island Review on December 18, 2014.

Since I wrote the essay, I’ve revisited Greece several times and have revised my somewhat harsh opinion of mastika. On our most recent visit to Athens, Maggie and I sampled a liqueur being served in the lobby of our hotel. Intrigued by its unusual flavor, I was astonished to learn that it was—you guessed it—my old acquaintance, rendered much more palatable with the addition of what I suspect was honey.

The Tears of Chios

Of all the disasters to have befallen Greece over the past few years, the fires that swept across southern Chios in 2012 were certainly not the worst. Yet they and the destruction they left in their wake are strikingly emblematic of the dangers that Greece faces in the opening years of the twenty-first century.

Chios is a mountainous island in the eastern Aegean that lies within sight of the Turkish mainland. It has passed through the hands of a succession of invaders—Persians, Romans, Byzantines, Venetians, Genoese, and Ottoman Turks—and was the scene of two terrible calamities in the nineteenth century. The Ottomans slaughtered tens of thousands of Chians during an uprising in 1822, an atrocity that rallied worldwide public opinion behind the eleven-year Greek struggle for independence and inspired Eugène Delacroix to paint his famous Scène des massacres de Scio. Chios would not become part of the modern nation of Greece until 1912, but in the meantime it suffered another devastating event—an earthquake in 1881 that may have claimed another ten thousand victims.

It was the Genoese, relatively benign rulers of the island from the mid-thirteenth through mid-sixteenth centuries, who organized and encouraged the widespread cultivation of Pistacia lentiscus. An evergreen that rarely grows higher than fifteen feet, the tree thrives throughout the Mediterranean region, but it is only in southern Chios and an adjacent stretch of the Turkish coast that it yields drops of the aromatic resin known as mastic.

□□□

Legend has it that Saint Isidore of Chios, a Roman naval officer, professed his Christianity to his commander while on the island and was subsequently beheaded when he refused to renounce his faith. At his death, the mastic trees growing in the southern part of the island are said to have begun weeping—hence the fact that you may still hear mastic drops referred to as “tears.” Today agronomists speculate that the area’s microclimate and its dry, limestone-rich soil are responsible for the aberration.

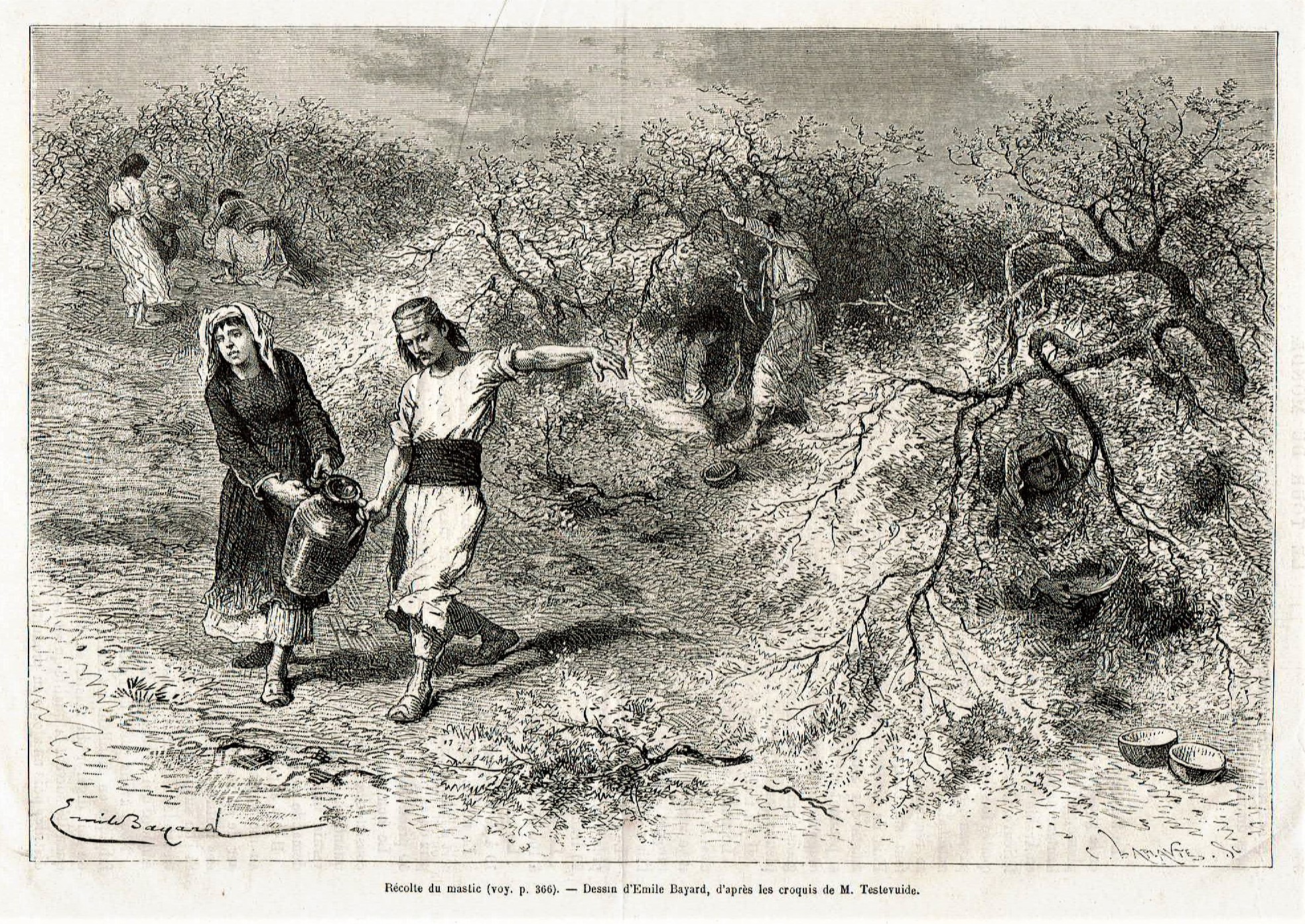

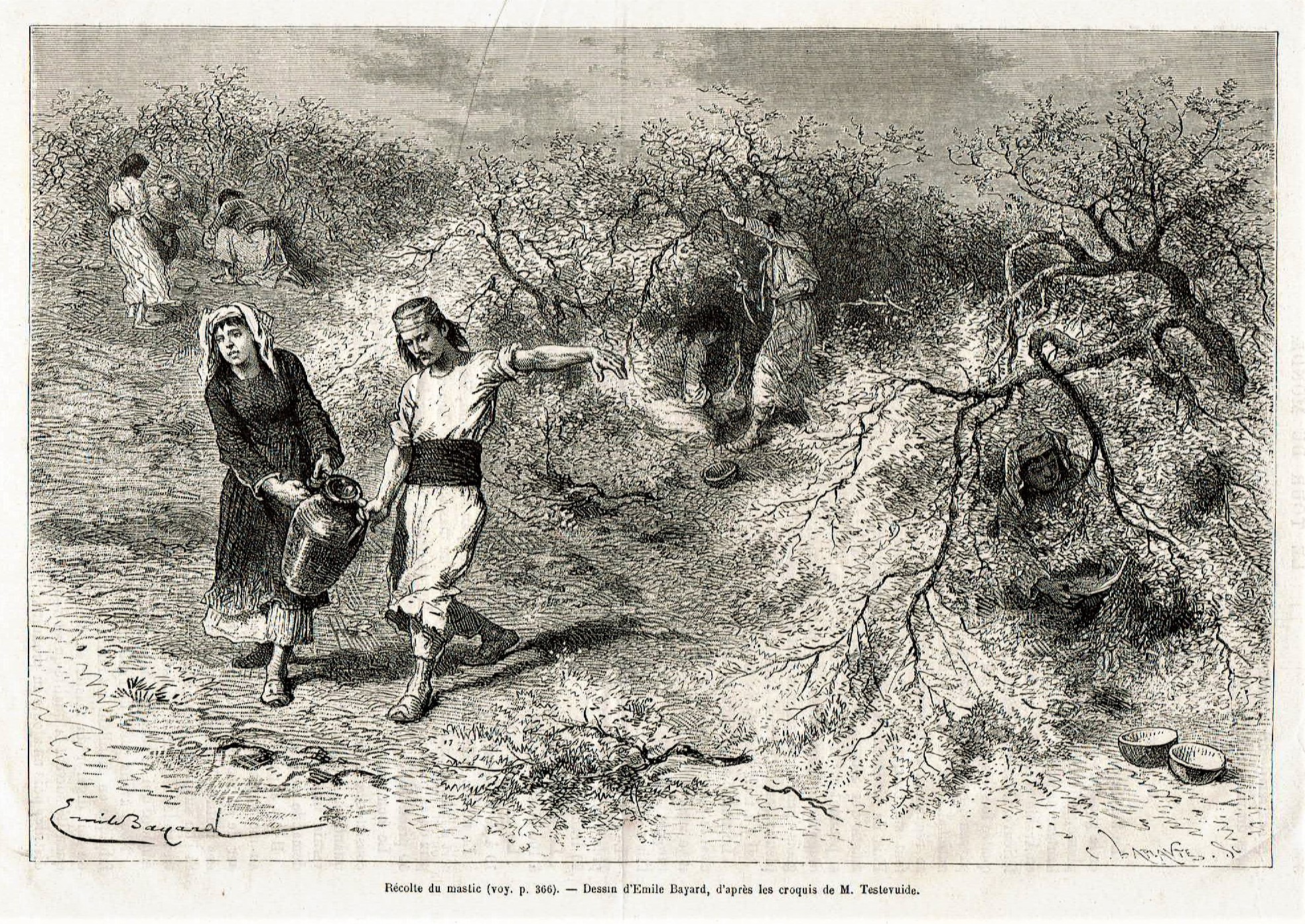

Mastic production is concentrated around some two dozen mastikahoria, or mastic villages, in southern Chios. Pruned and fertilized every winter, the plants begin producing mastic when they are about five years old. At that point villagers clear the ground beneath the trees and cover it with white clay. Then, over the course of the summer, they make multiple incisions in the branches. The resin seeping from these incisions falls to the ground and hardens over a period of fifteen to twenty days, after which the drops are collected in baskets, cleaned, and sorted.

Harvesting mastic is exhausting work involving methods that have scarcely changed over the centuries, but the substance is a precious commodity that has assured the island’s prosperity. Taking its name from the Greek word mastichein, “to gnash the teeth,” it appears to have been the original chewing gum, and in turn has given us our word “masticate.” Mastic is used throughout the Balkans and the Near East in various kinds of confectionary, including “spoon sweets.” These are thick, sugary pastes flavored with fruits or spices and typically served by the spoonful in glasses of ice water. Commonly known as “submarines,” such treats are the summertime favorites of Greek children. Mastic is also used to flavor a liqueur known as mastika, and recent studies suggest that mastic oil is an effective antibacterial and antifungal agent.

Mastic is routinely described as being “piney” or even “cedary,” and is something of an acquired taste in whatever form you sample it. In Reflections on a Marine Venus, his account of the two years he spent on the eastern Aegean island of Rhodes after World War II, Lawrence Durrell compared mastika to “horse-embrocation.” Yet the regional demand for mastic is great, with some 3,000 local families making a living and many more supplementing their incomes from its production. In recent years, shops specializing in mastic products have opened in larger Greek cities as well as Paris and New York City.

Ironically, the climate in which the mastic tree thrives also poses a grave threat. Although many parts of Greece experience torrential rains in fall and winter, summers are dry and are growing hotter. Wildfires burned their way across southern Chios in 1994, and according to early reports those that struck in August 2012 destroyed half of the island’s mastic trees within a few days. Due to widely broadcast scenes of rioting in Athens and Thessaloniki, tourism had already fallen to half its anticipated level on the island, and, coming as they did during Greece’s deepening economic crisis, the fires were an even greater catastrophe. However, some trees that initially appeared dead put out leaves and blossoms in 2013, and others were quickly replaced thanks to the Marfin Investment Group, which collaborated with Blue Star Ferries in purchasing 9,000 saplings from a local nursery and distributing them gratis to farmers.

For me, mastic represents a near-miracle of intense flavor drawn—perhaps “wrung” would be more accurate—from an uncompromising landscape under what are often harsh conditions. Greece itself has been involved in regional and worldwide conflicts throughout its modern history, and endured bitter civil wars during its fight for independence and after World War II. By 2013 fully a third of its citizens were living in poverty. Under the circumstances, the mere fact of the country’s continued existence seems miraculous. And so when the time comes for me to take down my bottle of mastika yet again, I’ll be tasting much more than just the resin of a strange tree from the other side of the world.

□□□

The hand-colored botanical illustration at the top of the page was engraved by H. Weddell from a drawing by G. Reid and appeared in John Stephenson and James Morss Churchill’s Medical Botany; or, Illustrations and Descriptions of the Medicinal Plants of the London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Pharmacopœias, published by Churchill in London in 1831. The engraving of the mastic harvest is by Emile Bayard after a drawing by Dr. Erhard Testevuide, and appeared in Testevuide’s article “L’Ile de Chio,” which was published in an 1878 issue of the French periodical Le Tour de monde.

□□□

If you’ve enjoyed today’s post, please share!