Grove Koger

Maggie and I recently spent two weeks in a rented house on Florida’s St. George Island, enjoying the luxury of doing nothing that we didn’t care to do.

Among St. George’s many attractions are its animals, particularly its birds. To some of you, the birds we enjoyed so much are common sights, species that you probably take for granted. But to us Idahoans, the cardinals and mockingbirds and red-bellied woodpeckers and white-breasted nuthatches that serenaded us every morning as we drank our coffee were a revelation—an exotic serenade that, despite its frequently cacophonous quality, was an invigorating and inspiring start to the day. (There were also the occasional cries and croaks of birds we were familiar with—crows and gulls and ospreys and great blue herons—as well as the enthusiastic guttural rasps of tree frogs when the weather was rainy.)

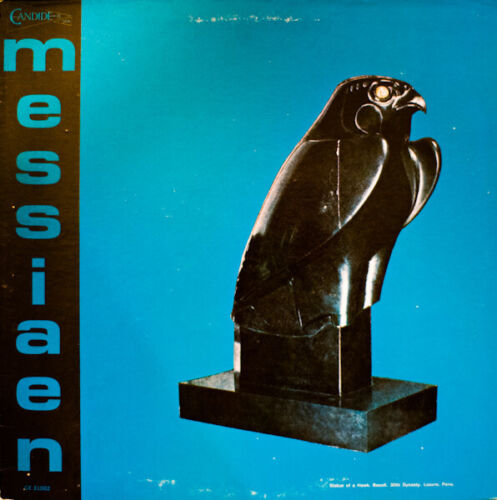

Again and again as I listened, I was reminded of the music of avant-garde French composer Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992), who was fascinated by birdsong. He notated and transcribed the songs of individual species as he traveled, and he ultimately incorporated such transcriptions into his compositions, including several cycles for piano—Catalogue d’oiseaux (1956-56), La fauvette des jardins (1970), and Petites esquisses d’oiseaux (1985). Among his orchestral works, the relatively short Oiseaux exotiques (Exotic Birds, 1953-56) in particular stands out for its exciting use of avian cries and calls and whistles and chatter.

The work is scored for solo piano, piccolo, flute, oboe, E-flat clarinet, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, bassoon, 2 horns, trumpet, glockenspiel, 3 gongs (high, medium, and low), snare drum, tam-tam (very low), temple blocks, woodblock, and xylophone. So prominent is the piano that Messiaen characterized Oiseaux exotiques as “almost a piano concerto.” The 18 species depicted—if that’s the right word—are indigenous to the Americas, China, India, and Malaysia., and include the Indian minah bird (heard first), the prairie chicken, the bobolink, and the catbird.

Messiaen also made use of rhythms from Greek and Hindu music, but such details are for experts. I’ll simply say that it’s a work that, to my ear at least, seems to lack the kind of development that I’m used to hearing in music. But the conclusion, which is made up of a series of harsh, repeated chords, is clearly a conclusion, and an exciting one.

You can listen to Messiaen’s one-time pupil Pierre Boulez, who also commissioned the piece, discuss and then conduct it here. But Boulez was an intensely cerebral interpreter, and I think that the performance he elicits is a little cold. More enjoyable is the version by the Ensemble Oktopus, which you can listen to here.

Messiaen once remarked that “among the artistic hierarchy, the birds are probably the greatest musicians to inhabit the planet.” So I urge you to sit back, clear your mind of whatever preconceptions you have about the way music ought to sound, and listen to the masters!

If you’d like to subscribe to World Enough, enter your email address below:

And if you’ve enjoyed today’s post, please share!