Grove Koger

When we paid a second visit to the little southern Portuguese community of Tavira in 2023, the sights we planned to revisit included the town’s handsome dragon trees.

Growing in a little riverside park a few hundred feet from our hotel, the two trees probably go unnoticed by most of the town’s residents and visitors, but they’re a botanical delight for those who pause to look at them carefully or take time to learn more about them.

The dragon tree, or Dracaena draco, is native to southwest Morocco, the island nation of Cape Verde, the Spanish archipelago of the Canary Islands, and the Portuguese archipelago of Madeira. Scientists think that it was introduced to another Portuguese archipelago, the Azores, by Portuguese travelers from Cape Verde several centuries ago. Over time, the widely separated populations have developed into several subspecies.

Dragon trees are evergreens with pithy trunks, and can reach as much as 60 feet or so in height and 20 feet in circumference. They also have an unusual and distinctive growth pattern. After ten or fifteen years, the tree blooms and grows multiple branches, each one of which then grows more branches after another long period, with the result that its crown spreads wider and wider, as if the tree were growing upside-down. As John Mercer writes in Canary Islands: Fuerteventura (David & Charles, 1973), the “dense vivid green upon the pale grey, with a patch of the darkest shadow on the ground below, make a fresh, cool sight even amongst the other trees.”

The trees’ small fruit have a red resin that was once used in pigments and traditional medicines. The indigenous inhabitants of the Canary Islands, the Guanches and the Canarios, carved shields from the trees’ bark, and I’m sure took advantage of the shade that Mercer refers to.

Reading about dragon trees in Visit Native Flora of the Canary Islands, by Miguel Ángel Cabrera Pérez (Everest, 1999), I’ve learned that a separate species of the tree has been identified on Gran Canaria Island and designated Dracaena tamaranae. This “new” species, found on the southern (and geologically oldest) section of the island, apparently shares characteristics with such East African species as Dracaena ombet and Dracaena schizantha, as well as an Arabian species, Dracaena serrulate. Botanists speculate that specimens may have reached the island millions of years ago in the Miocene period.

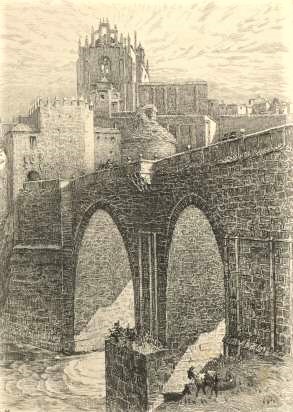

I don’t know when Tavira’s dragon trees were planted, but the oldest specimen on the Canary island of Tenerife is known as El Drago Milenario, and, at an estimated 1,000 to 5,000 years of age, it may be the oldest in the world. At 69 feet in height, with a circumference of about 66 feet, it may be the largest as well. That’s it you see above in a photograph by Mike Peel (www.mikepeel.net), reproduced courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. And should you find yourself on Tenerife, you can take a closer look by visiting the Parque del Drago, Icod de los Vinos, on the north shore of the island.

There was once another ancient specimen on the island, one examined by famed geographer and naturalist Alexander von Humboldt in 1799. Sadly enough, it was destroyed during a storm in 1867. According to John Mercer’s Canary Islanders (Rex Collings, 1980), the Guanches once “venerated” this particular tree, “seeing it as a protective spirit. Used by the Spaniards as a boundary post when dividing up the land amongst themselves in 1496 …, its well-authenticated measures were 75ft high, 78ft around the trunk.” Botanical artist Marianne North followed in Humboldt’s footsteps in 1875, discovering that the once-sacred tree had “tumbled into a mere dust-heap” with “nothing but a few bits of bark remaining.” However, she found “some very fine successors about the island,” one of which you see in her painting at the bottom of today’s post. And following in both sets of footsteps, A. Samler Brown added in the 1922 edition of Brown’s Madeira, Canary Islands, and Azores (Simpkin) that “a cutting [was] still growing in one of the conservatories at Kew.”

The many people who stroll by Tavira’s dragon trees probably take them for granted, but the trees are members of a distinguished family, and worthy of our attention.

If you’d like to subscribe to World Enough, enter your email address below:

And if you’ve enjoyed today’s post, please share!