Grove Koger

Today’s post reprints an article I wrote for Winter 2017 issue of the late lamented Laguna Beach Art Patron Magazine. It was a pleasure to research, and as usual on such occasions, I learned a lot.

□□□

The story of the Lone Woman of San Nicolas Island is actually two stories. One is a factual account of a woman who was marooned on an island off the coast of what was then Alta California, while the other is a vivid fictional recreation of the woman’s lonely plight and her evolving appreciation for the natural world. The first is frustratingly brief and ambiguous, while the second has become a modern classic.

The scene of the Lone Woman’s adventures was fog-bound San Nicolas, the most remote of the Channel Islands. San Nicolas was once inhabited by a group of people we’ve dubbed the Nicoleño, Native Americans whose numbers were decimated when Russian and Aleut fur traders began hunting the sea otters living in the island’s waters. In 1835 Catholic missionaries arranged with a schooner captain to transport the remaining inhabitants of San Nicolas to the mainland.

The story might have ended there, but for some reason the seamen left one young woman behind. Did she leap off the ship when she realized that her child was not aboard? That was the story that circulated decades later, apparently with no basis in fact. What we do know is that the wind rose and the ship’s captain had no choice but to cast off and abandon the woman.

It was only after 18 years—18 unimaginably lonely years—that Santa Barbara hunter George Nidever happened upon signs that someone was living on San Nicolas. He returned with several other hunters, one of whom encountered the woman skinning a seal. She “was of medium height,” Nidever wrote, and “rather thick.” He added that “she was continually smiling,” but that her teeth were “worn to the gums.” She obligingly helped the men hunt otters for several weeks, and left with them as the ship sailed back to the mainland.

No longer “lone,” the woman lived with Nidever and his wife, but no one, not even local Native Americans, could understand a word of what she said. Nevertheless she seems to have been delighted with what she saw—including children and horses—and danced to show her pleasure.

Fast forward a century and we find writer Scott O’Dell approaching the end of his stint as book editor for the Los Angeles Daily News. Born in LA on May 23, 1898, O’Dell had lived in San Pedro and on nearby Rattlesnake (Terminal) Island, worked as a cameraman in Hollywood, and hobnobbed with the likes of John Barrymore and F. Scott Fitzgerald. Then in his mid-fifties, he’d published a handful of books, but none of them had set the world on fire—a situation that was to change with the appearance of Island of the Blue Dolphins in 1960.

O’Dell had first heard of the Lone Woman in the 1920s. But it was only much later, in anger at the hunters who were slaughtering “everything that creeps or walks or flies” near his house in the mountains, that he began to rework the story in a subtly different form.

O’Dell transformed the Lone Woman into Karana, who jumps ship to remain with her abandoned brother, Ramo. However, Ramo is soon killed by wild dogs, leaving Karana completely alone. Yet she perseveres, making a simple but ultimately fulfilling life for herself. She survives on shellfish but spares larger animals, realizing that “the earth would be an unhappy place” without them. Instead she tames birds and two of the dogs as her companions. When she’s rescued at last and taken to the mainland, accompanied by her animals, she can’t help but remember “all the happy days.”

The fictional story ends there, but the factual one has a much less satisfying conclusion. After enduring years of solitude, the Lone Woman died only seven weeks after her rescue, apparently from the effects of the rich food suddenly available to her. Her real name had never been discovered, but she was baptized as Juana Maria by the fathers at Mission Santa Barbara and buried in an unmarked grave in the mission’s cemetery.

Island of the Blue Dolphins went on to win Scott O’Dell a host of awards, including the prestigious Newbery Medal for the year’s “most distinguished contribution to American literature for children.” Long since recognized as a children’s classic, it’s been translated into 28 languages, and its simple account of Karana’s stoic response to her situation has inspired millions of young readers.

In 2012, after years of searching the island, Navy archaeologist Steve Schwartz discovered what he believed was the cave that the Lone Woman had lived in. What clues to her ordeal might it reveal? However, the Navy, which administers San Nicolas, has ordered the work halted in light of protests by the Pechanga Band of Luiseño Indians, who claim a cultural affiliation with the Nicoleños. That claim has been challenged, but for the moment, at least, San Nicolas is keeping its secrets.

□□□

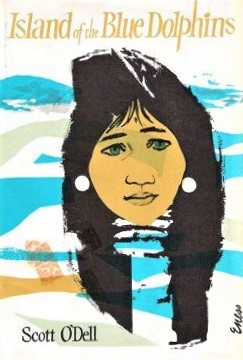

The image at the top of today’s post reproduces the cover of the first edition of Island of the Blue Dolphins. The map is reproduced from Wikipedia under the provisions of the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license, while the photograph of the island is also reproduced from Wikipedia, but under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license. The portrait of O’Dell is reproduced from A-Z Quotes, which doesn’t provide any further information as to its source.