Grove Koger

Today’s entry from my revision of When the Going Was Good deals with the most famous book by Wilfred Thesiger, who was born June 3, 1910, and died August 24, 2003.

□□□

Arabian Sands (London: Longman, 1959)

Wilfred Thesiger, whose father was ambassador to Ethiopia, was the first English child born in that country. He went on to record his delight in the culture and ceremonies of the pastoral, so-called primitive peoples of Africa and Asia, as well as an intense hatred of progress and the “drab uniformity” it engenders. Called by an admirer a “great crag of a man,” he reserved a particular antipathy for the internal combustion engine.

In the years after World War II, Thesiger undertook two extremely arduous journeys through southern Arabia’s Rub ‘al Khali, or “Empty Quarter,” which had been crossed for the first time by a Westerner—Bertram Thomas (1892-1950)—only fifteen years before. Thesiger was able to employ several of Thomas’s guides on his first journey (1946–47), although he took a slightly different route, beginning and ending his journey at the port of Salala on the coast of Oman. Among many other hazards, the trip involved at one point a stretch of two weeks between wells. Thesiger’s second journey (1947–48) took him along the western edge of the Empty Quarter and north to the shores of the Persian Gulf. Two further trips (1948–50) were confined to easternmost Arabia.

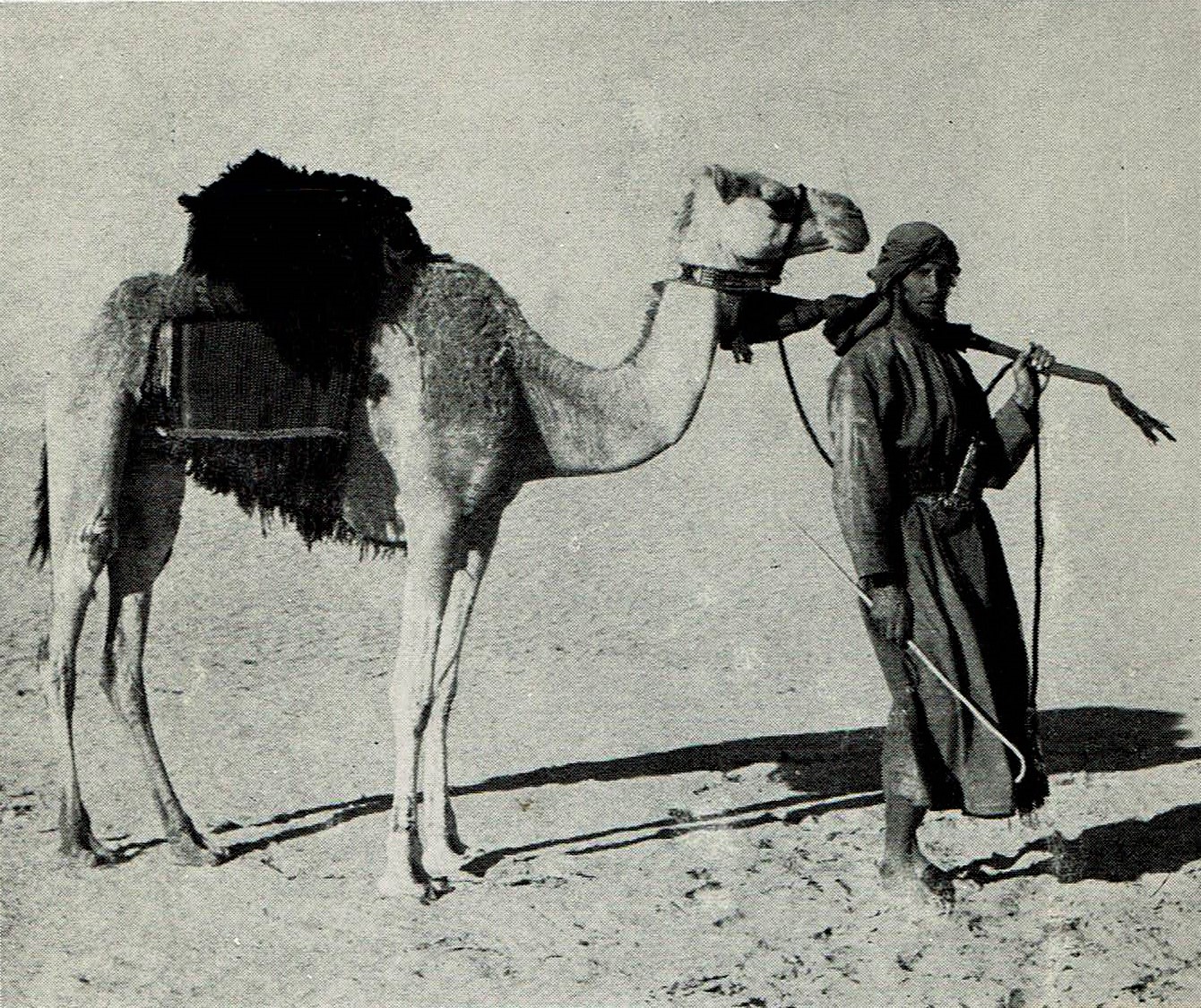

Arabian Sands was written a decade after these journeys, and memory seems to have imposed a certain clarity on the events that Thesiger describes, a quality suited to the extremes of geography, weather and behavior that he encountered. This quality is to be found as well in the striking photographs that illustrate the text. (Oddly enough, Thesiger’s hatred of things modern and mechanical does not extend to the camera.) Thesiger was publicly celebrated as the last of the great explorers, yet his writings make it clear that his journeys had an intensely personal meaning to him: “I believed … that in those empty wastes I could find the peace that comes with solitude, and, among the Bedu, comradeship in a hostile world.”

□□□

Other travel works by Thesiger include Desert, Marsh, and Mountain: The World of a Nomad (1979; also published as The Last Nomad: One Man’s Forty Year Adventure in the World’s Most Remote Deserts, Mountains, and Marshes); Visions of a Nomad (1987); The Life of My Choice (1987); The Thesiger Collection (1991); My Kenya Days (1994); The Danakil Diary: Journeys through Abyssinia, 1930–34 (1996); and Among the Mountains: Travels through Asia (1998).

For further information on Thesiger, I recommend Michael Asher, Thesiger: A Biography (London: Viking, 1994); Warwick Cairns, In Praise of Savagery; Mark Cocker, Loneliness and Time: The Story of British Travel Writing (New York: Pantheon, 1992); Alexander Maitland, Wilfred Thesiger: The Life of the Great Explorer; andRichard Trench, Arabian Travellers: The European Discovery of Arabia (Topsfield, Massachusetts: Salem House, 1986).

□□□

The image at the top of the post reproduces the cover of the 1959 Dutton edition, while the black-and-white photograph, taken from the same book, shows Thesiger during his second journey. The painting is a 1944 portrait of Thesiger by Anthony Devas and, as an artistic work created before 1969 and owned by the government of the United Kingdom, is in the public domain.